Franglais: An attitude of lingual laziness, a threat to the integrity of a language or simply a way to facilitate bilingual communication?

Throughout history, language has been the most genuine means of communication. It was, is and will always be indispensable, for as long as there is life. However, language isn’t just a “code”; it also contributes to the way we see the world. Some people even argue that we are spoken by language as much as we speak through it. Today, and ever since the world has become one big multilingual village, where different cultures live together, language has evolved into a far more flexible tool.

In an increasingly Americanized world, people on different sides of the globe are getting into the swing of incorporating American words or expressions into their mother tongue, instead of looking for equivalents in their language. A few years ago, a fierce debate over this issue found its place worldwide, and especially in France, with the country’s famous Franglais, with opposing perceptions. While some held a radical response to this sociolingual trend, viewing it as a threat to the integrity of the French language and a threat to their identity, others considered it an effective way of communication.

In an increasingly Americanized world, people on different sides of the globe are getting into the swing of incorporating American words or expressions into their mother tongue, instead of looking for equivalents in their language. A few years ago, a fierce debate over this issue found its place worldwide, and especially in France, with the country’s famous Franglais, with opposing perceptions. While some held a radical response to this sociolingual trend, viewing it as a threat to the integrity of the French language and a threat to their identity, others considered it an effective way of communication.

A portmanteau word combining Français and Anglais, the term “Franglais” was first coined by French grammarian Max Rat in 1959 in an article published in France-Soir, to describe the spontaneous attitude of blending American words or expressions with French, in one sentence. Then the term gained popularity in 1964, with René Étiemble’s book, Parlez-vous franglais?

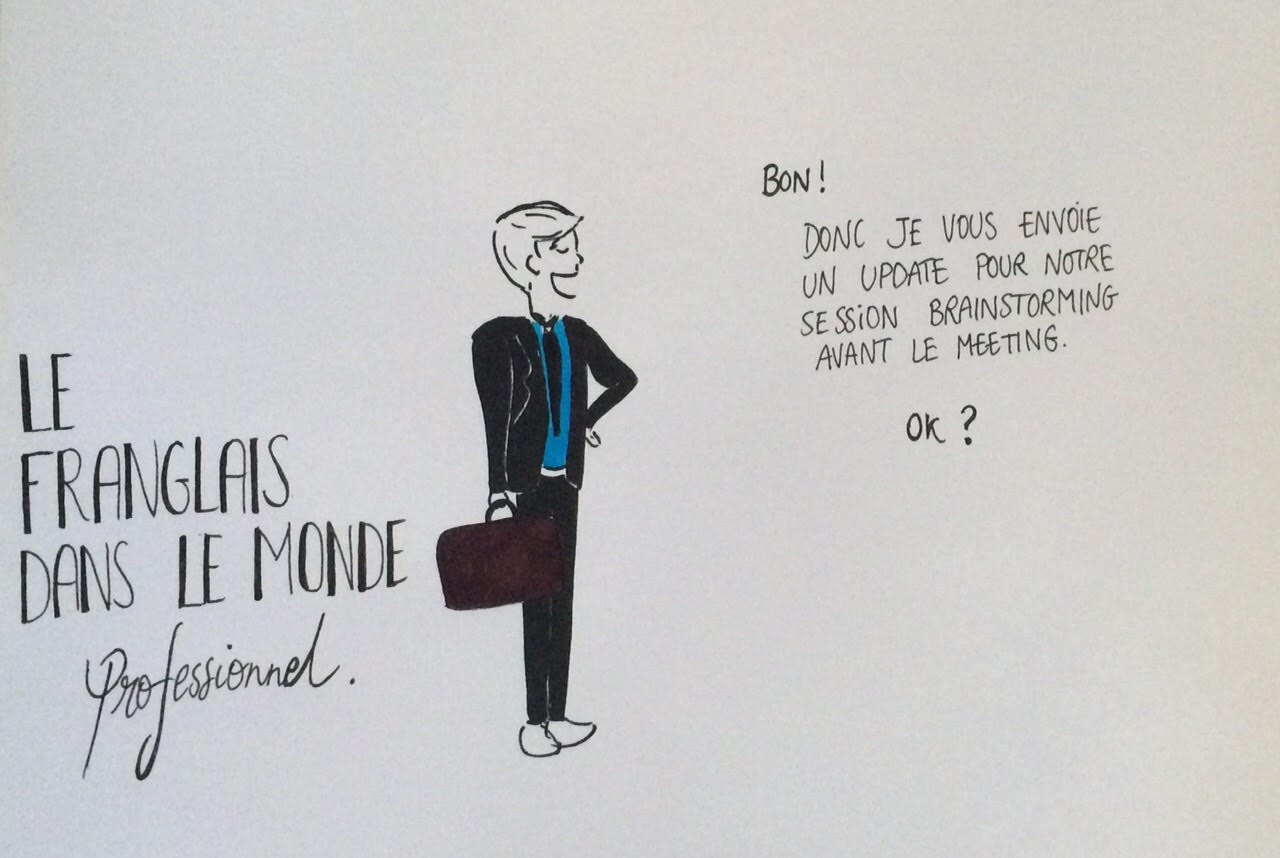

The phenomenon was accentuated by the dominance of English, via the trend towards an American Way of Life, but also with US progress in the fields of technology and business, and was spread widely through the young generations and into their jargon. Words like “cool”, “sexy”, or “cute” transcended US borders, into French. So a French actor becomes “super sexy”, or a baby “trop cute”. On Fridays people wish each other “un bon week-end”, and a young woman asks her friend if she wants to “faire du shopping”. Similarly, in the business arena, people would rather say “une séance de brainstorming”, or “J’attends votre feedback”, than stating it in their own language.

In sociocultural linguistics, this phenomenon is called “code-switching” (or alternating between two or more languages), and it distinguishes itself from other phenomena like “borrowing” (the technique of borrowing a word from one language and incorporating it into another without translation) or using “calques” (a word or expression borrowed from another language through literal translation). Since the 1980s, many linguists have regarded code-switching as a natural product of the use of bilingual language. The motives of this trend are now countless. For some people it is a way of fitting in, or showing off, while for most it is a way of filling the gaps when expressions for certain concepts are lacking, or when the word is not well known.

The “guardians” of French language, though, don’t care much about the motives. All they seek is to purify it from foreign imprints. To them, French is more than their language. It symbolizes their history. It defines their identity. This resistance to foreign languages goes back to the 1600s when the Académie Française – pre-eminent French council for matters pertaining to the French language – was founded to counter Italian influences, and which continues to fight against English-language influences today. Since then, French has been treated as an affaire d’état. For instance, the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie was created in 1970 in response to the Commonwealth. It represents “countries and regions where French is the first or customary language; and/or where a significant proportion of the population are [French speakers]; and/or where there is a notable affiliation with French culture”. Moreover, in 1994, the Loi Toubon was enacted, making the use of French compulsory in government, the workplace and state-funded schools. And the most recent action is the famous ban of the word “hashtag” in 2013 by governmental decree, replacing it by the French equivalent, “mot-dièse”.

But these attempts to protect French from other languages have proven relatively unsuccessful. In effect, English has already invaded la langue de Molière especially in the technology and business domains. English words have become not only part of the oral language, but have also found their way to French dictionaries, though known as Anglicisms.

But these attempts to protect French from other languages have proven relatively unsuccessful. In effect, English has already invaded la langue de Molière especially in the technology and business domains. English words have become not only part of the oral language, but have also found their way to French dictionaries, though known as Anglicisms.

In an ever-changing world, in which language is constantly evolving, linguists and lexicologists are questioning the way we view and perceive spoken and written communication. Many are arguing that language is a tool that aims to facilitate communication and cooperation between communities. If Franglais, Spanglish or other code-switching trends serve that purpose, then why resist them? It is definitely enriching to constantly create new words and expressions that fill gaps. This process, however, should be tolerant towards the coexistence of French with other languages. As such, Franglais wouldn’t be a threat to French; it becomes the ultimate trigger for French reinvention.

Links to related articles:

Language Mixing on the Rise: http://blog.dakwak.com/2012/10/language-mixing-on-the-rise/

Franglais row: Is the English language conquering France?: http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-22607506

Language barrier: French resistance to Franglais: http://www.thelocal.fr/20130204/french-language-franglais-culture-paris-english-protect-promote

Au revoir Mister Franglais: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/7221918.stm

Le Franglais: http://cmgsic.blogspot.ch/2010/09/le-franglais.html

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *